Is it time to retire the view that skill in baseball is measured by batting averages?

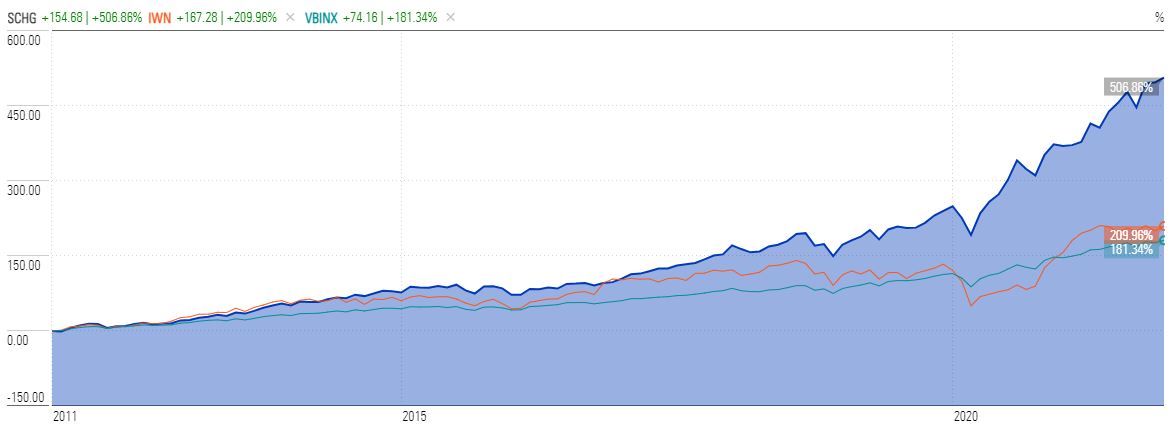

Benchmarking is a perilous exercise, especially holdings-based benchmarking, because it doesn't give you the big picture. It could lead you to think that the percentage of funds underperforming or outperforming their benchmarks even matters to you or your client's money. It's not your fault. We've been trained to think this way. It's clear, however, the area of large cap growth, despite all those underperforming fund managers in the category, has simply trounced the 60/40 stock/bond portfolio in recent years. Interesting, no?

Image: Prudent and diversified stock selection among the largest, strongest, most well-known large cap growth equities (SCHG, blue fill) has outperformed exposure to the two most widely-accepted quantitative explanatory factors to stock returns, small cap value (IWN, orange line), and the most widely-accepted standard asset allocation model, the Vanguard Balanced 60% stock/40% bond (VBINX, turquoise), by nearly 300 percentage points and approximately 325 percentage points, respectively, during the past 10 years. Image Source: Morningstar.

In his book, The Success Equation, Mauboussin also writes about the importance of differentiating between experience and expertise. He includes a quote from Professor Gregory Northcraft, a psychologist at the University of Illinois, in the book: "There are a lot of areas where people who have experience think they're experts, but the difference is that experts have predictive models, and people who have experience have models that aren't necessarily predictive (page 23)." He talks about the need for deliberate practice (the hard work and thousands of hours needed to master a skill), and how investors should seek to differentiate between experience and expertise to understand the value of predictions about the future.

---

One of the clear signs of expertise, for example, is one's ability to make accurate predictions, or use a model that effectively ties cause to effect.

In investing, for example, the Valuentum team has built and updated 20,000 discounted cash-flow models over nearly 10 years, testing cause and effect. Other firms may have done the same. One might conclude that this expertise alone may give a leg up on the experience of some investors that may just be passive onlookers of market price movements (even those watching for decades) or just crunching the numbers, making little connection between what actually drives stock returns.---

The Success Equation goes into many examples of how "statistical significance" is hurting many professional fields, perhaps one of my favorites a comical reference to a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal The Proceedings of the Royal Society B. You might have heard of this one. The work suggested that women who ate breakfast cereal were more likely to give birth to boys than girls. It's difficult to believe this "entertainment" gets published in peer reviewed journals, but such work may be no more significant than some of the most widely disseminated beliefs in finance, which brings us to the main point of this article.

---

Whether it's Nobel laureate William Sharpe's arithmetic (which can easily be dismissed by assuming one large investor underperforms leading to hundreds of smaller investors outperforming) or how Vanguard's founder Jack Bogle uses dividend yield as an incremental measure of total return (as opposed to capital appreciation that would have been achieved had the dividend not been paid) or the very basic construct of factor investing, itself, (which falls flat as most factors are based on ambiguous, realized and backward-looking data)--Mauboussin's take on the paradox of skill in investing is just as disappointing.

---

Let's define the paradox of skill first. The paradox of skill is the view that as more and more participants of a sport or business become more skilled, the variance between the outcomes narrows. It may be fair to say that the opposite may also be true. As more and more participants of a sport or business become less skilled, the variance between the outcomes might narrow (for example, if a group of Little Leaguers doesn't have the strength to hit homeruns, the league home run tally will converge to 0.). Mauboussin uses the examples of batting averages and earned run averages in baseball as well as marathon runners to illustrate his view. However, the author indicates that there are other endeavors such as professional basketball, where, as skill has improved, the variance of outcomes has actually increased.

---

At best, we think it's a mixed bag as to whether a paradox exists in sports. Mauboussin points to the high standard deviation of tall players as to why the paradox of skill may not be applicable to basketball players, but nonetheless, just like the paradox of skill may not be relevant to basketball (based on statistical observation), there may be plausible reasons why the paradox of skill shouldn't apply to other areas such as baseball or investing either (after perhaps correcting for other statistical variables). To name a few confounding considerations when it comes to the win-loss records in baseball: Players' level of skill varies through the course of the year, players get hurt and traded, and the season is just too long; even the best players have to sit out games. Statisticians cannot correct for all these variables and more.

---

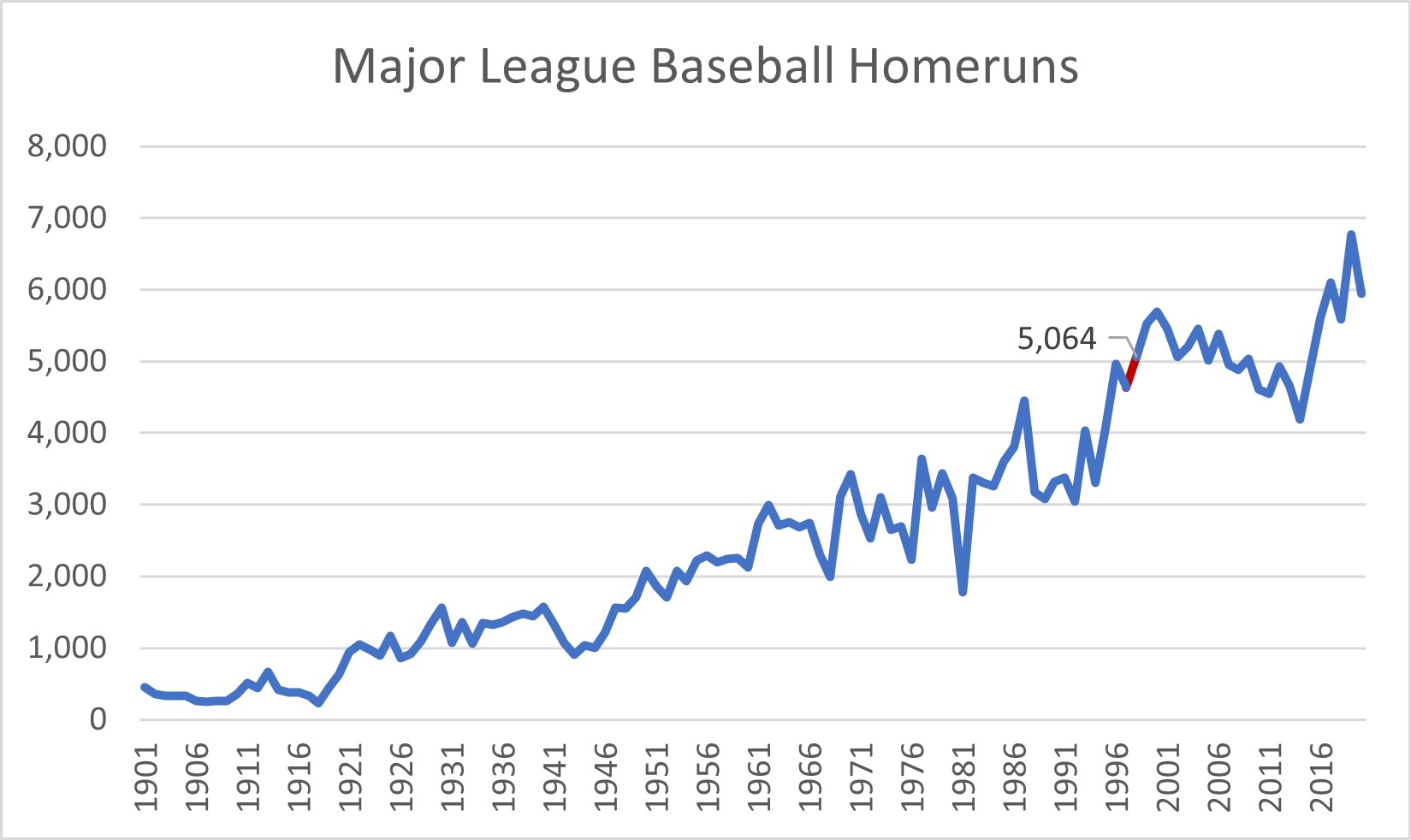

Baseball, however, is a great resource because it is a game of statistics. There's also the observation that over time, the variance of batting averages has shrunk as a basis for a paradox of skill. The justification goes that both pitchers and batters have become more proficient at their trades, cancelling out any improvements (and that as all batters have become more skilled in time, the variance in their performance has declined). But just like the standard deviation of tall players in basketball may help explain in part why the paradox of skill doesn't exist in basketball, the nature of batting averages in baseball might easily be explained by baseball players focusing more on hitting the long ball (homerun). Look at how the game has changed. Note how total homeruns have still marched higher after the league expanded to the current number of 30 teams in 1998 (red spot).

---

---

Image: The game of baseball has changed during the past 100 years. While many point to a declining standard deviation and coefficient of variation in batting averages for evidence of a paradox of skill in baseball, it's more likely the game has changed. Players are hitting more homeruns, sacrificing batting average as a result. Note the red part of the line is when the game of baseball expanded to the current number of 30 teams. Data from the COVID-19 shortened 2020 season omitted. Source: Baseball Almanac.

---

It's hard to make sweeping conclusions about luck and skill, and perhaps that's in part what we're saying. Maybe skill in baseball today is not measured by batting average, but rather by the number of homeruns one hits. It does seem more skillful to hit the ball over the fence and more about luck to have the ball land in between the foul lines without someone catching it on a fly and to reach first base safely without being called out. How many line-drives are outs and "Texas Leaguers" are hits, for example. Batting average is a lot about luck -- homeruns, not so much.

---

Everyone knows, too, that your swing will be a lot different if you're trying to poke one over the infield or slap one down the line for a hit than it would be in trying to hit the ball 450 feet in the left-center field stands. The Babe Ruth quote at the top of this article hits the nail on the head of what we're witnessing with respect to batting averages today (there is a big tradeoff between hitting for power and hitting for average), and why nobody has hit over .400 since Ted Williams in 1941. The incentives of the game of baseball have clearly changed to focus more on home runs. Look at this quote.

---

If you're 10 years old and your coach says get on top of the ball, tell him no. In the big leagues these things that they call ground balls are outs. They don't pay you for ground balls, they pay you for doubles and for homers. --

Josh Donaldson

---

The same is true with investing. The game has changed over the years and so have financial professional investor incentives, and arguably not in a good way. In the book, Mauboussin talks about agency costs that arise when a money manager has different interests than the investor. He references Charles Ellis, the founder of Greenwich Associates, in explaining how the "profession is about managing portfolios so as to maximize long-term returns, while the business (of investing) is about generating earnings as an investment firm (page 173)."

--

Today, agency costs are soaring as indexing continues to proliferate.

--

For example, it may be much easier for financial professionals to "mail it in" to grow their businesses by pursuing an indexed asset allocation portfolio for clients, while holding active management to holdings-based benchmarks, if only so they can market that active management doesn't have "skill" -- even as those "unskilled" active managers do significantly better than them! Outrageous, no?

---

Well, are these financial professionals really acting in their clients' best interests, or are they seeking to scale their own businesses with indexed asset allocation portfolios? Are they looking at the big picture when it comes to all options available for their clients, including stock selection? Are they thinking too much within the asset-allocation box or too much within the holdings-based benchmarking box? Do they even care?

---

There's all these potential conflicts of interest you may not even know about as an investor or advisor, but there's more, too. Simply put, it's very difficult to outperform the market consistently and over longer periods of time if one doesn't purposely try to deviate from the market. Today, however, as academic quantitative analysis proliferates, diversification has become not an avenue to achieve goals, but in some ways, the goal, itself! The ways of concentrated undiversified "true intrinsic value" investors such as Warren Buffett have become less popular.

---The statistical tendencies speak for themselves. Holding more than 20 stocks in a stock portfolio, for example, pretty much eliminates unsystematic (firm-specific) risk and

should push the returns of heavily diversified portfolios to the market average, reducing the standard deviation of excess returns.

Over-diversification is the enemy of outperformance (outsized standard deviation of excess returns), and the means by which to achieve mediocrity. Here's a quick take from Morningstar that hits the nail on the head on the risks of over-diversification:

---

While much of academia has focused on the risk of not being diversified enough, we believe that there's a practical risk to being too diversified. When you own too many companies, it becomes nearly impossible to know your companies really well. Instead of having a competitive insight, you begin to run the risk of missing things. You may miss something important in the 10-K, skip on investigating the firm's second competitor, and so on. When you lose your focus and move outside your circle of competence, you lose your competitive advantage as an investor. Instead of playing with weak opponents for big stakes, you begin to become the weak opponent.

---

The author, while highlighting in his own words in The Success Equation (see quote at top of this article) how stock portfolios have conformed over time due to a reduction of active share brought about by myriad influences in how active managers are "playing the game," doesn't emphasize enough what we believe is the correct conclusion for the observation of declining standard deviations of excess returns relative to holdings-based benchmarks.

---

Investors are conforming to a similar playbook due to conflicting incentives, and then they are being measured by holdings-based benchmarks that pretty much match their exposures. Oftentimes, active managers are even penalized if they deviate from their benchmarks (by allocators looking for targeted exposure), and sometimes and ironically, they are punished when they beat their benchmarks by too large of a margin -- because some may believe those managers are taking on too much risk. It's near-impossible for the standard deviation of excess returns to expand in such an environment.

---

But that's not all, however. Unlike his work in evaluating baseball and basketball, Mauboussin doesn't emphasize that active mutual funds and ETFs are only about 15% of the stock market, according to the Investment Company Institute. Perhaps putting all other arguments aside, analyzing the standard deviation of returns of 15% of the stock market, as in active funds and ETFs, tells us little about luck or skill in the world of investing. Mauboussin warns about the use of small sample sizes early in the book, but his very conclusion that a paradox of skill exists in investing, itself, is based on limited data. The book has only padded the marketing behind the index craze, too, making The Success Equation an unfortunate text, in our view.

---

Maubousin notes that famous researchers Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman wrote in their 1971 paper, "Believe in the Law of Small Numbers," that humans have "'strong intuitions' that are 'wrong in fundamental respects,' a shortcoming 'shared by naïve subjects and by trained scientists.' The flaw, simply stated, is that (humans) have a tendency to believe that a small sample of a population is representative of the whole population (page 216, 217)." In this case, humans believe that there is a paradox of skill in investing based on a small sample of the population, the 15% of the stock market that makes up active fund managers. With that said, here is what could actually be driving the reduced standard deviations among excess returns, from

Value Trap:

---

The peculiar connection between 1) the propagation of spurious (quant) factors, 2) quant's influence on fundamental investment frameworks (e.g. some fundamental value investors think in terms of quant value factors)--an effect that reduces the dispersion of skill and returns as professional approaches become more congruent and undifferentiated (think conformity)--and 3) severe active fund underperformance [in part, because of holdings-based benchmarking] during the past 15 years is the primary reason why (we) do not believe professional active investors are becoming more skilled, and that's why they are underperforming [their benchmarks] after fees, as outlined in the popular "paradox of skill" thesis. [Professional active investors may actually be becoming less skilled as quant and passive investing proliferates.] (Our) view [instead] is that, as indexing and factor investing proliferates, alpha may actually (be) shifting from professional active investors to other parts of the stock market [as Sharpe's arithmetic may imply on a grander scale]. For example, other investors--defined as hedge funds, pension funds, life insurance companies, and individuals by the Investment Company Institute--hold roughly 70% of the stock market, as of 2019. Households own about 30-40% of the stock market, by some estimates. [We posit simply that wider dispersion of returns can be found in the other 85% of the market not impacted by the various factors outlined in this article.]

---

There's a lot of informational value in reading The Success Equation (and everyone should pick up a copy), but please be careful to come to your own conclusion. From where we stand, there is not a paradox of skill in investing (or baseball, for that matter). The games have simply changed based on new incentives. Some wise person may have written this before: Be careful not in what you read, but rather in the conclusions you draw from your reading. We wish Mauboussin could re-write The Success Equation considering some of the thoughts in this article. Maybe he will!

---

---

(1) https://www.valuentum.com/articles/asset-allocators-fail-advisors-should-pick-stocks-save

---

---

It's Here!

----

Tickerized for holdings in the DIA.

---

----------

Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free.

Brian Nelson owns shares in SPY, SCHG, QQQ, DIA, VOT, BITO, and IWM. Valuentum owns SPY, SCHG, QQQ, VOO, and DIA. Brian Nelson's household owns shares in HON, DIS, HAS, NKE. Some of the other securities written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies.

"If I'd just tried for them dinky singles, I could've batted around .600." - Babe Ruth

"If I'd just tried for them dinky singles, I could've batted around .600." - Babe Ruth

1 Comments Posted Leave a comment